Dismantling the railway in the border region is a matter of political courage. Imagine that you are guarding a house with five doors. Only one of them is used, but the others are left unlocked. Wouldn’t it be easier for you to guard the house if you locked or even bricked up the extra doors?

This is how reserve captain Mārtiņš Vērdiņš figuratively describes the discussions about dismantling the Baltic railway connection with Russia and Belarus in an interview with Delfi.

The National Armed Forces (NBS) are continuing to prepare an in-depth assessment of this issue, which will be submitted to the Cabinet of Ministers by the end of the year. Meanwhile, politicians are already sending signals that these “doors” will most likely remain open for now.

Discussions about dismantling the railway tracks and embankments to Russia and Belarus arose after the TV program “Nekā personīga” reported at the end of November that the NBS insisted on such a step because they pose a military threat. Namely, railway tracks in Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania are of the so-called eastern or 1520 mm gauge.

Tracks of the same gauge have been built throughout Russia, which actively uses its railways to support its invasion of Ukraine. “The opinion of our armed forces is that every railway line connecting us with Russia is one line too many,” said Māris Tūtins, head of the Information Analysis and Management Department of the NBS Joint Staff, quoted in the broadcast.

Currently, Latvia is connected to Russia by two rail corridors and to Belarus by another. Both in the broadcast and in discussions and statements afterwards, representatives of various political forces rushed to take a position – some said that all rail connections should be dismantled as soon as possible, others that this would be a crime against the national economy, as the flow of goods from Central Asia and other countries depend on railways. In other words, there is a risk, but should the railway really be dismantled in a hurry? We will discuss this further.

The meeting of the Baltic presidents in Riga in early December seemed to put an end to the discussions. At a press conference, the presidents stated that the dismantling of the railway, if it happens, must be a joint decision by the Baltic states. “If we do it, we will do it together,” said Estonian President Alar Karis.

Latvian officials also promise to evaluate a separate report on the possible impact of railway dismantling, which has been commissioned from several ministries and security agencies. It should be ready very soon, by the end of 2025. While we wait for it, Delfi approached several military analysts and economists with a request for comment.

The idea is not new

Reserve Colonel and military analyst Mārtiņš Vērdiņš explained to Delfi that the idea of dismantling the railway tracks and embankments to Russia is nothing new – it has appeared in various military defense plans since the 1990s.

“You’ve probably heard the argument that we have forests, lakes, swamps, and other natural features that protect us from the east. That’s true, but railroad tracks are highways that cut through all our defence lines.”

With Latvia’s accession to NATO, the idea of dismantling the railway temporarily lost its relevance in the minds of military leaders, because “we thought that this shield was impenetrable,” explained Vērdiņš. Similarly, the volume of transit cargo transported by rail from the east to Latvian ports was much greater at that time than it is today.

However, if the main counterargument against demolition is now economic considerations, then it must be understood that not all railway lines need to be demolished at the same time, emphasizes Vērdiņš. During the Soviet era, Latvia’s railway network was built with the aim of transporting 100 million tons of cargo per year, but today we transport only a tenth of that. Therefore, the railway demolition “project” can be divided into stages without damaging the economy.

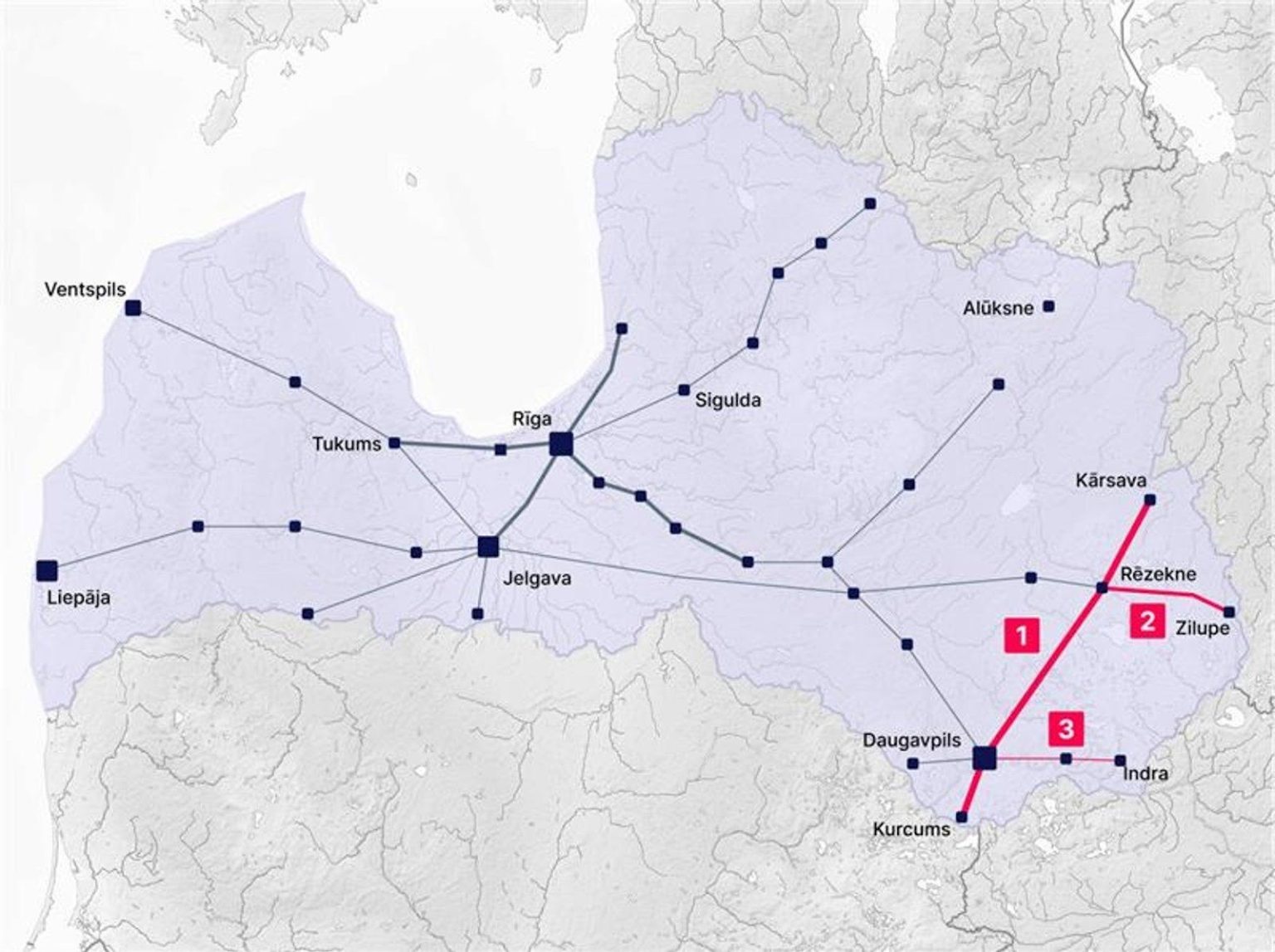

In Vērdiņš’s view, the first line to be demolished should be the Kārsava-Kurcums railway line, which divides Latvia’s most eastern Latgale region into two parts, crossing it from Russia to Lithuania, because in the event of war, this line would be a “godsend” for the invading forces advancing on Riga from the east, allowing them to easily supply their troops along the entire length of the front.

The second line would be the railway line that enters Latvia from Russia via Zilupe and leads to the port of Riga, while the third connection, which enters Latvia from Belarus via Indra, could be kept as a functioning transport artery, while preparing it for rapid demolition on the eve of a real military escalation. Why? In the hope that Belarus may still try to remain neutral and not get involved in Russia’s attack on NATO.

Vērdiņš also repeatedly emphasized that public discussion is unjustifiably focused only on the dismantling of the tracks. The Russian armed forces have a railway unit consisting of 30-50 thousand people who are specially trained in combat conditions, namely, to restore destroyed railway tracks during artillery fire and air strikes. If only the tracks are destroyed, it takes this force only a few hours to restore them.

If the embankment on which the tracks ran has also been destroyed, and thoroughly so, with the rubble taken away and scattered elsewhere rather than simply piled up nearby, then restoring the railway is a matter of days or weeks. “Of course, everything can be restored, but it takes time, and it is precisely this delay that we need,” he emphasized.

We protect the house with holes

Vērdiņš predicted that both Russian and Chinese agents of influence in Latvia and companies that still profit from transit would lobby against the dismantling of the tracks and embankments, so “it won’t be that simple.” “I don’t think we’ll get any further than discussion at this point. But I would like to note one thing – if the Estonians start doing something like this and we don’t, then that’s bad,” said Vērdiņš.

Why Estonians, not Lithuanians? Because Lithuania must ensure rail transit to the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad – dismantling this railway line in peacetime could indeed be a casus belli, or a pretext for war, so it must be kept functioning until the very end, explained Vērdiņš.

“Let’s imagine that you are a guard in a house with five doors. Only one of the doors is used, but the others are left open. As a guard, you are constantly rushing around. The best thing you could do would be to at least lock the extra doors, or better yet, block the doorways with bricks. Then, even if Lithuanian transit to Karaļauči remains, but we get rid of all the other open doors, we will have made our task much easier,” he concluded.

But what about mines?

We also contacted Jānis Garisons, former State Secretary of the Ministry of Defense. He said that the railway issue is important, but should only be considered in conjunction with other border protection plans. “It sounds a little strange when we say that, on the one hand, it is not relevant for us to mine the border now, and that building border fortifications is not so urgent, and then suddenly we focus on one element that is only part of the whole concept,” he said.

In Garrison’s view, the railway is not a route of invasion, but rather a route for supplying the army – as was the case in Ukraine in the early days of the war. Accordingly, railways are an important issue, but an equally important issue is minefields to stop the first invaders at the border. “I have heard the argument that the border should not be mined because we will manage to do it. Excuse me, but in my opinion, it is much quicker to dismantle the tracks and embankments than to mine the border, which will take months,” he said.

Garrison also pointed out that the positions of the rail tracks must be “marked” so that, in the worst case scenario, they could be blown up by our own artillery, but the mines still need to be purchased – they are not readily available on the market. Only the NBS could say exactly how long it would take to dismantle the tracks and mine the border.

The backbone of the Russian army

Meanwhile, the NBS told Delfi that an in-depth assessment of future steps to strengthen anti-mobility is currently underway. The deadline set by politicians for the assessment to be ready is the end of 2025. The content of the assessment: “The NBS is responsible for providing a military assessment of the time and resources required to dismantle the railways and embankments on the eastern border, as well as possible alternative actions that could achieve a similar military effect.”

“The railway is the backbone of the Russian army’s logistics, and the NBS is convinced that, in the event of an attack, the enemy would also plan to use the tracks on Latvia’s eastern border for its own purposes.

In its in-depth assessment, the NBS will inform the Cabinet of Ministers about various possible solutions to prevent the enemy from using the railway in the event of an attack,” the response to Delfi states.

Are officials quietly hoping that the war will end soon?

But how big would the impact of rail transport disruption be on Latvia’s economy? Would it have such tragic consequences that it really should be left as a last resort? Economist and investor Ģirts Rungainis believes that the impact would be measurable in tenths of a percent of GDP. By showing that we are prepared to fight to defend ourselves, we reduce the risk of Russian aggression. Which would cause greater damage to Latvia’s economy: a full-scale war with Russia or a reduction in rail transit?

“We are in a place and situation where we cannot achieve ideal solutions. We have to take what is less bad. At the moment, transit and cooperation with Russia are at their lowest point in 20 or 30 years. Of course, this still provides jobs and income for a certain number of workers and entrepreneurs. But the main threat to Latvia’s economy is military conflict with Russia in the Baltic region. This means that during this period, until a new international security structure and situation in Russia has been established, this is the main economic consideration. All other considerations are secondary,” he explained.

Rungainis reminded that the transit sector in Latvia has historically been closely linked to politics in general, as well as to the Ministry of Transport and the civil service of state-owned companies subordinate to it, making it very difficult to introduce changes to the status quo that are unfavorable to the sector. “I think that attempts to postpone solving the problem have been going on for a long time. There is a quiet hope in the Ministry of Transport and Latvijas Dzelzceļš that Russia’s war in Ukraine will end soon, in some way,” he said, pointing out that the main opinion on this issue should therefore be that of the NBS.

“The beautiful future Russia”

Politician, economist, and guest lecturer at the Stockholm School of Economics in Riga, Vjačeslavs Dombrovskis, shared similar thoughts.

He admitted that he was not sufficiently informed about military aspects to unequivocally support one course of action or another, but from an economic point of view, a distinction must be made between the short term and the long term. In the short term, trade with aggressor countries is morally unacceptable, so the economic impact of stopping it is not taken into account.

The arguments about transit to Central Asia are stronger, but again, it should be remembered that this trade tends to be fictitious. “You can see from the statistics that trade with Central Asian countries, including Kyrgyzstan itself, has increased several times over since 2022. It is clear that this is not trade with Kyrgyzstan, but with Russia itself, which is hiding behind Kyrgyzstan’s identity,” he pointed out.

It is clear that the interruption of transit would cause economic turmoil while labor and capital moved to other sectors. This, in turn, would mean suffering and possible emigration for people who lost their jobs and income. However, in the long term, the economy would adapt to the new situation, Dombrovskis predicted.

“If Alexei Navalny’s followers win and create what they call ‘a beautiful future Russia’, then transit could resume. And then we’ll talk again about the costs of putting those tracks back in place.”

But aren’t those hopes a bit naive at the moment? “We have to allow for that possibility. For example, if we talk about Nazi Germany, it was difficult to imagine in the 1940s, but by the 1960s everyone was trading with Germany. It is clear that it will take some time, most likely many years, and the tracks will be needed again. Therefore, this is primarily a question for military experts,” Dombrovskis pointed out.

The fate of Kherson

Will politicians really take the military’s opinion as the main one, or will they be afraid to rock the economy in an election year? The government will decide on this in early 2026, when the report is ready, but we will most likely never know all the arguments that were raised in the debate. Transport Minister Atis Švinka (Progressive Party) said on December 11 on the program “Spried ar Delfi” : “These issues are never discussed in public in the government.”

From the minister’s statement, it could be inferred that the Ministry of Transport would not support the dismantling of tracks and embankments. Namely, the ministry will provide data on the impact on the national economy of “taking one step or another,” and these amounts are said to be “significant.” Švinka referred to the example of Finland, which has completely closed its border with Russia, leaving only the railway as the sole exception, which is “to be dismantled, blown up and liquidated in a short period of time.”

However, Vērdiņš was skeptical about such a plan in an interview with Delfi: “Those who say that we will go and blow things up when the time comes should bear in mind that Russia’s Spetsnaz and GRU forces were created specifically to clear mines before the war, prevent the destruction of important transport routes, and preserve them for the needs of the attacking army.

Relying on the fact that we will be able to blow everything up at the last moment is a very huge risk.

I invite you to remember the Antonov Bridge over the Dnieper River, which the Ukrainians had to blow up at the beginning of the war, but they did not manage to do so, as a result of which they lost Kherson and the entire region, which they then regained only with great difficulty.